In acknowledgement of Indigenous Peoples Day on Oct. 10, Belmont University dedicated its new Indigenous Garden—located next to the Foutch Alumni House— to celebrate and honor the ancestors, heirs, descendants and living members of the Cherokee, Shawnee, Chickasaw and Yuchi peoples who once occupied this very land.

The area surrounding the garden was filled with faculty, staff, students, alumni and community members who hastened to honor this new sacred space, as birds chorused nearby, as if to provide an intentional and melodical score for the afternoon’s event. Charles Robinson, founder of The Red Road and a member of the Choctaw tribe who spoke at a Chapel earlier in the day, opened with a beautiful prayer in Cherokee, that set the tone fitting for such a reposeful, commemorative event.

Research indicates that the land where Belmont now sits was once a hunting ground for these tribes, who also may have cultivated parts of it. By recognizing their first history on the land, Belmont’s Faculty Senate Memorial Committee sought to honor these people and acknowledge the losses they have suffered and the injustices they continue to endure. The garden is the result of more than two years of efforts from faculty, staff, students, alumni and community partners.

Dr. Beth Ritter-Conn, assistant professor of religion in the College of Theology and Christian Ministry, spoke at the event and said, “This project was initially called a memorial garden, but it quickly became clear to the members of the committee that it needed to be so much more than that. Cherokee, Chickasaw, Shawnee and Yuchi Peoples are not just characters and stories from the past. They are living, breathing people. Our friends, neighbors, colleagues, students, classmates, part of vibrant communities.”

In July 2020, Belmont’s Faculty Senate issued a charge to the Faculty Memorial Committee to sponsor the development of a monument memorial or marker to address “the relationship between the land on which Belmont sits — along with all the institutions that have been on it — to the practices of slavery, white supremacy and racism.” This required that the committee be both tenaciously honest and courageous in their thoughts and actions, including the recognition of the Native American inhabitants, enslaved people who lived and worked on the property, the various forms of racially segregated education, and the continuing efforts to take account of these parts of our heritage.

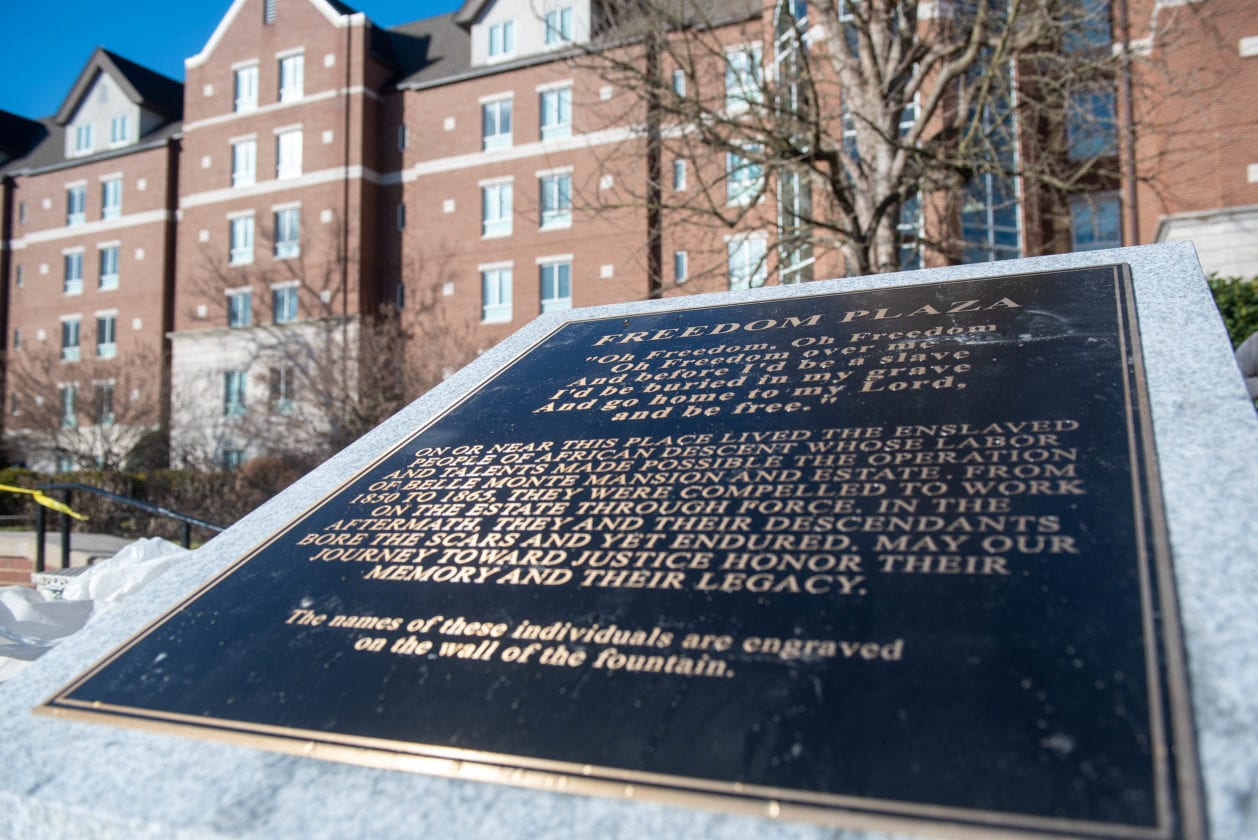

Phase one of this charge was executed in January 2021 with the dedication of Freedom Plaza which commemorates the lives of the people who were enslaved on this property. The fulfillment of the second phase was carried out through the dedication of the Indigenous Garden.

The Committee worked alongside Belmont’s landscaping and grounds crew to begin to understand how to fill the garden with plant life, prioritizing historical connections to key species. With more than two dozen types of plants thriving in the space, the Garden is home to Blue cohosh, blue wild indigo, butterfly, milkweed and goldenseal—all of which would have been used by the indigenous peoples to treat everything from toothaches to cancer.

Melissa Finan-Demalon, Belmont manager of landscaping and grounds, explained the process for selecting the plants and the boulders that surround them, along with her passion for the project. “The indigenous peoples believe in a connectedness and oneness with the natural world. They won’t end up as medicine, but perhaps these plants will serve another purpose for all that visit here in years to come,” she shared. “I hope that this garden will be a place where visitors might spend some time in the beauty of these plants and feel that connectedness and in that way, perhaps find a few moments of peace and grace that might provide a different kind of healing.”

Savannah McNabb—a Belmont alum, registered member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and Self-Determination Specialist with the Bureau of Indian Affairs—spoke of her time at Belmont as a Native American student navigating the world of college at a predominantly white institution.

“I joined the Chinese Cultural Association and that really taught me to look beyond the lens of our differences,” she said. “Although my culture is quite different from that of the Chinese culture, I also found similarities. Through my classes in global leadership and other student organizations, I was able to find my place at Belmont.” Through beautiful storytelling and sharing her experiences, she highlighted that the garden could provide the same for the Belmont community – an opportunity to understand our differences, come together and recognize our lives as a broader part of a community.

Following a beautiful rendition of Amazing Grace, sang in the Cherokee language by Gary White, Faculty Fellow in Watkins College of Art and member of the Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama, Belmont President Dr. Greg Jones closed the ceremony with a declaration of hope. Noting the power of peacefulness that comes with opportunity to simply reflect he said, “My hope is that this garden will be a place where repentance meets healing and hope and mutual understanding for a brighter future for all of us.”

Plans are in the works for how this garden may be further developed over time, including a series of invited speakers and art installations from indigenous artists, an informational website and other thoughts. The first addition to the garden is a plaque that reads:

“This garden acknowledges the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Shawnee and Yuchi peoples who once flourished on the land where Belmont University stands. The use of native plants and natural materials honors these indigenous communities’ reverence for the natural world and their resilience in the face of loss and injustice. Here, repentance meets gratitude and hope around the sacred waters of life.”

The dedication was followed by a reception at the Bell Tower Plaza.